The character of immigration to Greece radically changed after the outbreak of the economic recession in 2009 which is still continuing and constitutes the main expression of the deep crisis of reproduction of capitalist social relations in Greece. Fewer and fewer immigrants enter Greece after 2010 with the expectation to find a job and stay in the country, as it was the case in the previous period of capitalist growth. On the contrary, in the previous years most of the immigrants crossed the Greek borders in order to continue their journey towards other EU countries, and primarily towards countries of the European North. The main difference with the past is the inability of Greek capital to use this labour power in order to increase its profitability and expand its reproduction, in the context of the reduction of the total fixed capital in Greece. In this historical conjuncture immigrants cannot be used by the Greek capitalist state in order to promote the restructuring of the labour market, the broadening of the divisions within the working class and the increase of the rate of exploitation. In a country with 25 % unemployment, the new immigrant population is redundant for capital.

However, things are different in the countries of northern Europe and particularly in Germany, where the unemployment rate has fallen to 3.9 % (June 2017). Not all of the 1.2 million immigrants that arrived between 2015 and 2016 in Germany will manage to stay there, but the hundreds of thousands that will remain are not considered as redundant population. On the contrary, think tanks like OECD claim that the current labour market conditions in Germany are very favourable for the new immigrants since “Germany has one of the lowest unemployment rates in the OECD, coupled with a demographic outlook that is already starting to affect the labour market by smaller incoming cohorts of youth”.[1] What is important for the German state is the control and disciplining of the immigrants through an “integration policy” aiming ultimately at their integration in the German labour market as cheap labour power. This may be a long process since, according to surveys, it takes about 15 to 20 years until the employment rates of the immigrants reach those of the local proletarians.

It is questionable, therefore, to argue that the consolidated surplus population rises uniformly and linearly in every national social formation independently of the specific conditions of the expanded reproduction of capital which vary historically and geographically.

Usually, the comrades who argue that the basis of the European politics of migration control “is an overwhelming surplus of labour power” and that the “need [of the European states] for cheap labour seems rather limited”[2] do not take into account that the existence of surplus population is sine qua non for the expanded reproduction of total social capital since “the unrestricted activity [of capital requires] an industrial reserve army which is independent of the natural limits [of the increase of population]”.[3] Further, relative surplus population is instrumental for the profitability of capital since it plays a significant part in the moderation of wages and in disciplining the employed part of the proletariat. As Marx writes in the first volume of Capital: “The industrial reserve army, during the periods of stagnation and average prosperity, weighs down the active army of workers; during the periods of over‐production and feverish activity, it puts a curb on their pretensions. The relative surplus population is therefore the background against which the law of the demand and supply of labour does its work. It confines the field of action of this law to the limits absolutely convenient to capital’s drive to exploit and dominate the workers”.[4] On the contrary, they emphasize an interpretation of the “absolute general law of capitalist accumulation” according to which the expansion of the accumulation of capital leads inevitably to the continuous expansion of the “consolidated surplus population” and of pauperism. However, Marx noted that “like all other laws, it is modified in its working by many circumstances”, e.g. it requires the monotonous increase of the value composition of capital, which is highly debatable. According to Bue Hansen these circumstances include “the periodic devaluation of labor to the point that labor renders highly mechanized production uncompetive, which would lower the organic composition of capital; the declining birthrates, which Marx does not take into consideration as he methodologically takes demographic growth a variable dependent solely on wage levels. Thus, because of deindustrialization, declining birth rates due to women’s struggles for reproductive health and refusal of child bearing, violent state suppression of birthrates, etc. – it is possible that the tendency towards surplus population is periodically reversed. Further, the available pool of labor has historically been diminished by war, epidemics, famine and the slow death of poverty, declining public health standards and deadly policing of poor neighborhoods and borders”.[5]

If we take a look at the ILOs statistics on global workforce it seems that all the forms of existence of the global surplus population have remained relatively stable during the last 25 years.[6] What has changed is the distribution of industrial employment in “developing” and developed countries.

Layers of the Global Working Class, 1991–2015

Layers of the Working Class in Developed Countries, 1991–2015

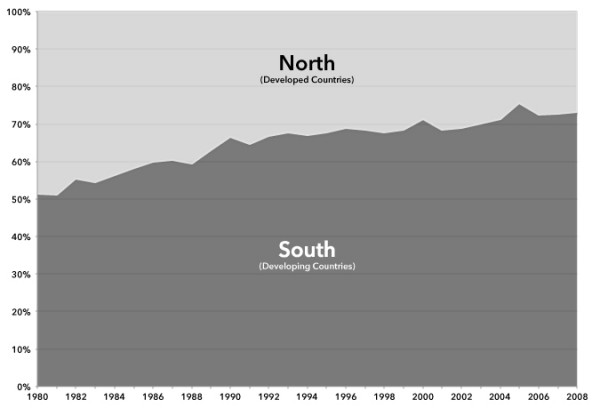

Distribution of Industrial Employment, 1980–2008

Consequently, we should seek a different explanation for the European politics on migration control. On the one hand, the number of immigrants crossing the European borders started to grow excessively and to create significant housing, boarding and policing expenses, as well as the possibility of a stir from the extreme right anti‐immigrant political forces and, on the other hand, the Schengen Agreement was called into question –due to the different politics on border and migration control which correspond to the different economic and political conditions in each European country– a development which would have extremely negative consequences for the European and the German capital. Furthermore, since a great number of immigrants successfully managed to enter Europe, the European governments were obliged to set limits to the expectations of the immigrants and to transform their sometimes radical collective energy through the lengthy, wearisome and even torturous procedures of registration, asylum application etc. into an individualized and precarious existence.

In our opinion, there are two issues of interpretation concerning the hostility of a part of the German and, more broadly, of the European working class towards the immigrants. First, the argument about “the systemic antagonism between surplus and potentially surplus proletarians”[7] cannot explain why there is also a part of the European proletariat which provided help to immigrants, even if such activities were philanthropic to a large extent. This fact puts on the table the question of ideology, of politics and, more broadly, of the public sphere as necessary forms of mediation between the objective course of capitalist accumulation and the constitution of proletarian subjectivity. In this context, we believe that the relation between, on the one hand, the reduction of the benefits of the capitalist welfare state to the proletarian citizens and, on the other hand, their hostility against undocumented immigrants or even immigrants coming from poorer European countries, who are accused of being welfare parasites, should be further investigated. In Greece, for example, the anti‐immigration sentiment has been bolstered up due to the ill‐willed resentment of the less well‐off workers (“The state didn’t help me when I was in trouble. Why should it help them?” is a common line of argument among such workers). The same ideological arsenal had been used against the poorer recipients of the welfare benefits in the countries of the developed Western world in order to legitimate the restructuring and the reduction of the so‐called social expenses of the state.

Also, we are obliged to comment on the critique to the position of the autonomy of migration, since it is a position that we have supported in our analysis. Of course, we agree that a big part of the immigrants crossed the European borders in order to flee the misery of war. However, they did not remain docilely within the refugee camps in Turkey. These people took the decision to put once more their life in danger and to clash with the European police and border authorities in order to seek a better life than a wretched survival within the Turkish camps. Moreover, if this issue is examined from a more theoretical standpoint, the border regime per se is exactly the obstacle which is set against the uncontrolled movement of proletarians, the method for their containment within a geographically specified regime of their subsumption as labour power to capital. The global flow of capital necessitates the control and restriction of the freedom of movement of the proletarians. The goal of the border regime is to permit only the disciplined mobility of the commodity labour power according to the fluctuating needs of capitalist accumulation. This subjection of the freedom of movement of proletarians is not something that may be ensured only through the “silent compulsion of the economic relations”. The direct use of violence remains necessary. And this violence represses the proletarian movement which becomes autonomized.

Finally, regarding the question of the development of struggles around the common class interests of local and immigrant proletarians we believe that the search for an immediate class interest is futile. However, for this very reason we cannot expect “the continuous [immigrant] influx from completely devastated parts of the world market” to call “attention to the necessity of a concrete upheaval”[8] as a purely objective development. On the contrary, as Marx wrote, workers must “learn the secret of why it happens that the more they work, the more alien wealth they produce, and that the more the productivity of their labour increases, the more does their function as a means of the valorization of capital becomes precarious”, they must “discover that the degree of intensity of the competition amongst themselves depends wholly on the pressure of the relative surplus population”. Therefore, they must “try to organize planned co‐operation between the employed and the unemployed in order to obviate or to weaken the ruinous effects of this natural law of capitalist production on their class”.[9] In this respect, the development of the common organization of struggles for the satisfaction of needs, i.e. the development of the form of mediation and communication between the separated parts of the class, is an issue of vital importance, even if the conditions for such an attempt are adverse.

Antithesi, August 2017

[1] OECD, Finding their way, Labour market integration of refugees in Germany, March 2017.

[2] Friends of the Classless Society, Workers of the world, fight amongst yourselves! Notes on the refugee crisis, November 2016.

[3] K. Marx, Capital vol. 1, Penguin, 1976, p. 788.

[4] Ibid., p 792.

[5] B. Hansen, Surplus Population, Social Reproduction, and the Problem of Class Formation, Viewpoint 5, 2015.

[6] R. Jamil Jonna and John Bellamy Foster, Marx’s Theory of Working-Class Precariousness, Monthly Review 67(11), 2016. Certainly, these figures downplay the actual size of the surplus population since the “wage workers” category includes a part of temporary and part-time employment. However, in India for example, the proportion of casual workers as a percentage of waged employees has fallen between 1983 and 2012 from around 68.8% to around 61.3% (source: Srivastava, R. 2016. Structural change and non-standard forms of employment in India, Conditions of Work and Employment Series No. 68), whereas in the OECD countries the average rate of temporary employment has risen from 9.26% to 11.79% and the average rate of part-time employment has risen from 13.6% to 16.83% in the same period (source: https://data.oecd.org). On the one hand, the increase of low-skilled jobs in the service sector and the decrease of manufacturing jobs explain the increase of temporary and part-time employment in developed countries. On the other hand, the decrease of the share of casual labour in India is explained by the shift in the workforce from agriculture to services and manufacturing which led to an increase of regularly employed workers. Such trends reveal the complexity and the uneven character of the formation of global surplus population.

[7] Friends of the Classless Society, Workers of the world, fight amongst yourselves! Notes on the refugee crisis

[8] Ibid.

[9] K: Marx, op.cit., p. 793 (our emphases).